|

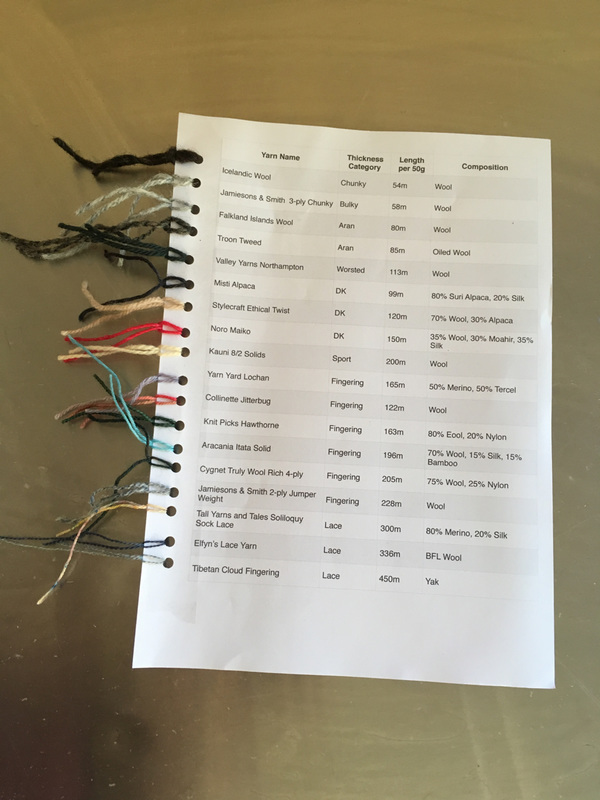

This is another part of my Spinning With a Purpose series of posts. Missed the others? You can find them here. I'm off to Scotland this weekend to run 2 workshops. One is brand new and based around spinning hand dyed fibre, the other is fast becoming my most requested workshop, aimed at getting spinners to really think about the yarn they're producing, and being more confident at matching it to a project. The other posts have shared the swatches I created as teaching tools, but this time I'm going to show you one of the most useful things I think I hand out to hand spinners. I started getting in to all things yarn related by learning to knit, and because I learned at a time when online shopping, and online knitting communities were just being started I became exposed to a vast variety of yarn. Probably far more than I would have done without being online. I had a reasonable sized budget for yarn, and used to enjoy spending it! I bought all sorts from many different sources. As a result I got educated pretty early on just how varied commercial yarns really are. I also developed a pretty good handle on just how thin or thick different yarn categories are, and how sometimes yarn companies are rubbish at classifying their own yarn. I got confident making yarn substitutions from those listed in the pattern, and that is a really useful tool as a hand spinner, as you're never going to be using the exact yarn the pattern asks for. During my workshop I get people to look at the structure of these commercial yarns. We also look at their comparative thicknesses, and discuss how metres per 100g is not always a good indicator of thickness. It's also why doing a straight yarn swap without thinking about what the original yarn called for in the pattern doesn't always work.

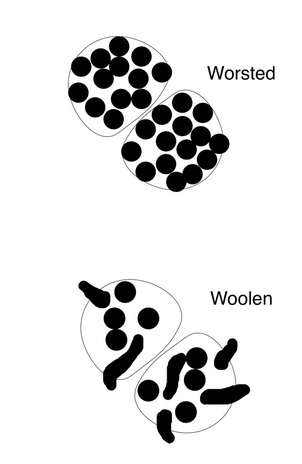

This sample card contains yarn of a full variety of thickness, yarn structures, and fibre compositions. It's a really handy tool to keep around purely as a reminder of how commercial yarns can be so very different. It's also a good control card, if you want to spin the equivalent of a commercial sock yarn you really do need to spin something incredibly fine. When I spin for a specific pattern I usually look carefully at the original yarn the pattern was designed to use. If I'm knitting colour work then I know I need a yarn similar to Jamiesons and Smith 2-ply Jumper Weight, if I'm knitting socks then I need to match something like the Knit Picks Hawthorne, or for a truly hard wearing yarn something of a similar construction to the Aracania, or an Opal sock yarn. So if you have a commercial yarn stash, maybe pull off a few centimetres and start making your own sample card. If you don't, but know you want to spin for a specific pattern, and are really not sure what the original yarn is like it might be worth investing a few pounds in buying just one skein/ball. Or ask around, why not do a commercial yarn sample swap at your local guild. Classically speaking there are 2 types of yarn. Woolen spun, and Worsted Spun. Back in "Ye Goode Old Dayes" all spinners would process their own fleece (or have a small child, or hefty man do it for them; more on that later...) and then use one of 2 spinning types to produce 2 very different yarns. Roll forward to modern times, and the wider variety of spinning fibres we have on offer and things aren't quite so clear cut, but Woolen and Worsted are still useful things for todays spinner to wrap their head around. It's a wordy blogpost, and heavy on video content, because nothing beats seeing these techniques carried out. We'll start off with what the yarns feel like. Woolen yarns contains lots of air, they're light, fluffy, and will often have small ends of fibre poking out of the yarn structure. They're incredibly elastic and bouncey. Jamiesons and Smith 2-ply Jumper weight is a classic commercial example of this type of yarn. Worsted yarns are smooth and dense, they tend to drape well and be much more lustrous. Many commercial yarns are spun in this way, particularly sock yarns. The 2 skeins below were spun using the 2 different techniques, you can can see how much smaller the woolen skein is, but when held under tension will stretch out to the same length as the worsted skein. Why are they different? Well it's all a matter of different fibre preparations, and different spinning techniques. Woolen spun is traditionally spun from carded rolags (this was the job small children carried out). It's then spun with the twist entering the drafting zone in a long draw technique. This video of a Navajo Weaver has long been a favourite of mine. You can see her producing rolags, and then using a navajo spindle to do a form of long draw. Carding, and the rolling in to a rolag creates a spiral of wool fibres wrapping round the tube. You then spin using a long draw technique that maintains that rolled structure. The yarn isn't smoothed, it's simply stretched out like a piece of chewing gum, that traps lots of air in the yarn, and makes it very bouncey and elastic. There are various form of long draw, some make more air filled yarns than others, but the one thing they have in common is that drafting backwards motion, allowing twist to enter the drafting zone. As a beginner it can require a bit of faith, we're generally taught to spin using a short forward draw, where letting twist past our front pinching hand can make it very hard to draft. This method requires twist to be be present however, as it's the twist in the drafting zone that controls the yarn thickness. Once you get going it's very easy to make a surprisingly consistent yarn using this method, as the yarn thickness almost becomes self controlling. Twist naturally navigates to thinner points, and those parts won't draft out further as they have enough twist to hold together. The thicker parts have less twist, and as you pull back they will become thinner, the twist travels in to them and the yarn becomes even. Historically this yarn was spun on Great Wheels. These wheels existed long before wheels with treadles, and because one hand was required to turn the wheel you needed to do a single handed drafting technique. They were an incredibly efficient way of producing a lot of yarn, very quickly. Long draw is still may favourite technique when I need a quick skein of yarn. Worsted Spun requires a very different fibre preparation, and spinning technique. While woolen spinning is all about trapping air, worsted does the exact opposite. Instead of carding the fibres they're combed. Hairs are aligned to be parallel, instead of being rolled up to perpendicular to the direction of the yarn. Twist isn't allowed in to the drafting zone, and a short forward draw is used (this is the most common technique most modern spinners use). Combing was traditionally done on large heavy combs, and was done by men. These are actually a scaled down version of the historical combs, but having handled a pair I can tell you that they're still seriously heavy to handle. As modern spinners we can now get some much smaller and lighter combs, but combing is still a real physical workout. No need to go to the gym if you do an hours wool combing!

So what about for the modern spinner? If you're willing to process your own fibres then you can create a true worsted or true woolen fibre. Providing you're willing to get the wool combs, or the carders out. However, what if you only want to work with commercially processed fibres, or prefer to drum card? In between the 2 true extremes of worsted and woolen is a sliding scale going from fluffy and air filled, to dense and lustrous. You can mix and match fibre preparations to dictate where your yarn falls on that sliding scale. Commercial combed top (the sort that most dyers use even if they call it roving) is most similar to the hand combed top. If you spin using a short forward draw you will make a worsted yarn. If however you spin from the fold the individual hairs will be bent in half and you start to trap more air in the yarn. Throw in a long draw drafting technique and you can still make commercial combed top in to a surprisingly lofty yarn. If you make faux lags and spin long draw you can start to head towards something that looks and feels very similar to a yarn made from carded rolags. Carded Batts are a hard one to wrap your head round. We tend to hear carded, and think of the rolags we make from hand carders, but when you really look closely at a carded batt the fibres run parallel along the length of the batt. If you just pull off strips and spin from one end then the yarn structure will be much closer to worsted than it is to woolen. However, all the same tricks you can employ to alter combed top apply to batts as well. True Roving is a bit tricky to get hold of, but wonderful to spin. It's a commercially processed fibre, but rather than being combed it's carded and peeled off the carding drums in a long spiral of fibre. The way that it's made tends to trap more air in it than combing, I tend to think of it as a halfway house between commercial combed top and hand carded rolags. Spun with a short forward draw it will still contain fibres that are mostly running parallel to the yarn length, but when spun using long draw you can create a yarn with a lot of air trapped in it. So what difference does it make, why bother to think about spinning technique and processing type before spinning?

Because it can make a massive difference to the type of yarn you can produce. Comparing a woolen spun yarn and a worsted spun yarn is like comparing chalk and cheese, they feel so very different and will do different jobs. A lace patterned shawl will have its holes more obscured by a woolen yarn and it won't hold a good block, but a jumper made of worsted spun yarn can be very dense and heavy, particularly in thicker yarns. It's worth doing a bit of experimenting to seeing how a fibre behaves when you spin it using different techniques. Both swatches below were spun from BFL commercially combed top. The Woolen one was spun from fauxlags using a long draw technique. The Worsted one was spun from the end of the top, using a short forward draw. As ever, pictures only say so much, you need to feel these yarns to really appreciate the difference. Over on the Hilltop Cloud Ravelry group a discussion topic popped up about ply number, and what would be best for a cardigan with cables... Of course common wisdom is that you should use 2-ply for lace, and 3-ply for cables. But a picture speaks a thousand words. These are all swatches I made up for my Spinning with a Purpose workshop, over time I'm sharing the swatches on via a series of blogposts, you can read the previous posts here. We'll start off with the lace. Here's a side by side shot. 3 ply is on the left, 2 ply on the right. Same thickness of yarn, same needles, but the holes are definitely more visible on the 2ply swatch, and the decrease columns more visible on the 3ply swatch. Close up of the 2-ply swatch. You can see at the point where the strands wrap over at the yarn over they nestle together. 2-ply yarn isn't actually round, it's more like an oval shape that spirals, that allows the strands to sit together nicely. In contrast on the 3-ply swatch those twisted sections take up far more room, and that means the hole you create from the yarn over is far less visible. What is very apparent though is how much that centred double decrease pops proud of the surface, and that feature is what makes 3-ply yarns a star for cables and textured stitches. Texture is very hard to see in photos, trying to demonstrate just how good a 3-ply is at cables is somewhat tricky, I wish you could all feel these swatches for yourselves. This is a standard 3x3 cable, together with a column of twisted stitches. In both cases the motif really pops off the surface of the knitting. In the 2-ply it's ok, partly because I like a firm tension for my knitting, but it lacks that 3-D pop. A shot from side on hopefully demonstrates what I'm on about... 3ply on the left, 2 ply on the right. It's not that the 2-ply version is rubbish, just that it lacks the wow factor that adding the extra ply produces.

So there you have it, sometimes the collective wisdom is wrong, but in the case, most definitely not. 2 ply for lace, 3 ply for cables! One of the things I refer people to most often is the piece that I wrote about plying twist. (Not read it yet? You can find it here, go read it and then head back to this post). Plying twist gets much easier to judge as you become a more experienced spinner. In general, most people don't use enough plying twist. When I first learnt to spin I was taught how to do a ply back test. The one where you take a length of singles and let them twist back on themselves, then use that to judge your plying twist. What I failed to pick up on was that you have to do that test with freshly spun singles. Even singles that have sat on a bobbin for a couple of hours won't give you an accurate measure of plying twist. Some of my first "proper" skeins... the singles were pretty good, but the plying job was just plain shoddy! However, I knitted with it and was pretty happy with the finished shawl. So with that in mind, just how important is plying twist in a finished fabric.... The Underplayed fabric is actually really nice, it has a nice feel to it, doesn't really suffer from biasing, if I hadn't labelled carefully I would be hard pressed to tell the difference between that and the one with a balanced ply. The singles I used were actually from the same bobbin I used for the singles swatch in the last blog post. The only disadvantage will be long term, the lack of plying twist means the ends of the fibres aren't as tucked in to the yarn. Over time it will be more prone to pilling, and won't wear as well. The over-plyed swatch however has the opposite problem of the swatch made from singles, it skews, though this time in the opposite direction. It also feels harsher, stiffer, and just not as nice. I bet it will wear very well though... Here's a close up of the skeins, left is under-plyed, centre is balanced, right is over-plyed.

How do you make sure you get it right? When you're spinning pull off a small section of singles. Break the singles being sure not to let any twist escape. Fold it in half, then let the single wrap around itself. Tie a knot in the end and put it in a safe place! When you start plying find your sample, and use that to judge the plying twist. Be sure to take a look at the yarn after it goes on to the bobbin as sometimes the stuff by your hands is ok, but as it winds on you can alter twist slightly. As I might have mentioned previously, there's been lots of behind the scenes stuff going on recently. One of which has been developing a new workshop. There's a lot that goes on when I come up with teaching ideas. After all there's a whole day to fill, and I like to make sure it's done professionally. That means writing a plan, creating visual aids, and quite often coming up with samples to show to people. It takes days when I add it all up (good job I don't really, I teach because I love it, rather than because it makes any sort of monetary sense!) The latest workshop I've developed is called Spinning with a Purpose, and it's designed to get people to think about their yarn rather than just spin something and hope it works. It focuses on woollen vs. worsted, the effect of ply number, and why sampling is a "good thing" particularly when spinning for a garment. We also dissect lots of commercial yarns to really work out what the industry means when it describes something as DK weight. There's quite a lot of things that we're always told are true, but it's nice to have concrete proof in front of you, so to that end I've been spinning and knitting a small mountain of swatches. ,In an ideal world nothing beats handling them to really get a feel for how they work as fabric, but I thought I'd share them via the blog as well. There are a lot, so this will be a semi-regular series of posts for a while. One of the things that I hear quite often at guilds when I visit, and read even more online, focuses around leaving singles as singles. A single is just 1 ply, just one length of yarn. It will be what is sat on your bobbin before plying. Singles yarns are great, they're quick to spin, make a lovely fabric, but they are something you have to plan for. And it's the planning part that I wanted to illustrate with swatches. I always sound like a bit of a grumpy guts when I tell people that if they want singles yarn they need to have spun it with an appropriate level of twist for it to be a singles yarn. If you intend to ply, then your singles need enough twist for them to hold together during the plying stage. That level of twist will be much too high for you to be able to use the singles without plying. Not unless you want a fabric that looks like the one above. That swatch was square when knitted, there are no sneaky increases and decreases hidden the borders! Twist is stored energy, and when you knit with it that energy causes the fabric to lean more in one direction. It means that any item you make will also lean and twist. If you spin a yarn intending for it to be a single you put in less twist, the yarn will always be unbalanced, as normally you ply to even out the twist energies. But if you spin for a single the twist level is significantly less, and the final fabric will have minimal skewing and twisting. And no, you can't just hang the singles up with a weight dangling from them. The only people who should treat yarn that way are weavers. If you're a knitter hanging a weight from your yarn as it dries will just cause you even more problems. As soon as you get that yarn wet again you reactivate all that twist, and the item will be just as skewed and twisted. So in short, don't do it! If you want to spin singles you need to plan to spin singles, not just decide to do it later because you can't make a decision about plying. Here's a close up of the singles used to knit that swatch. They're not exactly mega twisty...

I tend to like my yarns when the singles aren't too tightly spun, and tend to put slightly more plying twist in. Purely personal preference, but I find it gives me a nice durable fabric as the ends of the fibres are trapped by the other ply, but it's still soft due to the lower twist in the singles. If spinning singles sounds like your sort of thing then the Winter 2015 edition of Ply magazine is a must read. You can buy it direct from the Ply magazine shop, or if you're in the UK or Europe it's cheaper to go direct to Janet at the Threshing Barn. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

Hilltop CloudHilltop Cloud- Spin Different

Beautiful fibre you'll love to work with. Established 2011 VAT Reg- 209 4066 19 Dugoed Bach, Mallwyd, Machynlleth,

Powys, SY20 9HR |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed