|

We're all so used to be able to turn on a tap and get as much water as we want... Clean, ready to drink, and in plentiful supply. Our main complaint is usually that it doesn't taste very nice in certain parts of the country. However, we're not on mains water supply, neither are any of our neighbours, or many of the rural properties in this part of Wales. We all rely on springs, wells, streams and lakes. Normally this isn't a problem, this is Wales, water is one thing we have in plentiful supply, it's one of our biggest exports. If you live in western England then part of your supply probably comes from Welsh reservoirs. Then this happened... a miserly 2mm of rain in 3 weeks. Streams started emptying, springs ran dry. Normally reliable water supplies no longer existed. Luckily, we seem to have a spring that is well supplied, and thankfully we never ran out water. Though thankfully we fixed our leaky pipe in early June... Our water supply system is old, and for a long time we'd had a very damp patch in the garden. We presumed it was a spring, but when all the other damp patches in the garden dried up we did some investigating. The copper pipe that brings the water to the house had developed a huge hole... It's now all replaced with brand new plastic pipe, that doesn't leak, and will last a very long time. This is the marsh that supplies our water. Under all this reed grass are 2 plastic pipes with holes in them. The water seeps in and runs in to a collecting tank. At this stage it's still swamp water, but underneath the deposits that have built up over decades the water is actually remarkably clear and clean. Even better, despite the dry weather, it's still running! That trickle provides our water supply. Enough water for 3 adults to do all their household activities, and for me to run a dyeing business. Pretty incredible really. From that collecting tank a pipe runs downhill. This photo really gives a sense of how steep the valleys are in this part of Wales. The storage tank is just visible; the wooden fencing to the left of the green bush. This tank holds our water supply, it means that we can do all the normal daily things, even though the water is only a trickle. The tank empties during the day, then overnight fills back up again. We upgraded the old 1000L tank with a 2500L tank a few years ago. The old tank now sits in the garden so we can water plants in dry weather. This big tank is set up with an overflow system. In winter a pipe takes the water back to the stream that the spring normally flows in to. In summer we can bypass that system, and bring the overflow directly down to the garden. Even throughout the dry spell we've had a trickle of water much of the time that we've been able to use to keep things alive, and ensure the fruit bushes still crop. From that tank, another pipe flows down to the house (this is the one we replaced this year), and it gets cleaned and filtered. (the blue pipe in the photo is the overflow going to the stream) A UV light kills all the bacteria and viruses, and there's also a pH filter to clean out any sediment, and to lower the pH. Our water is naturally around pH 6, and will slowly dissolve all the copper pipes in the house if it's not raised. The water is also very rich in iron (that's what the black deposits are on the side of the collecting tank). Our kettle doesn't fill up with limescale... we get iron-scale!

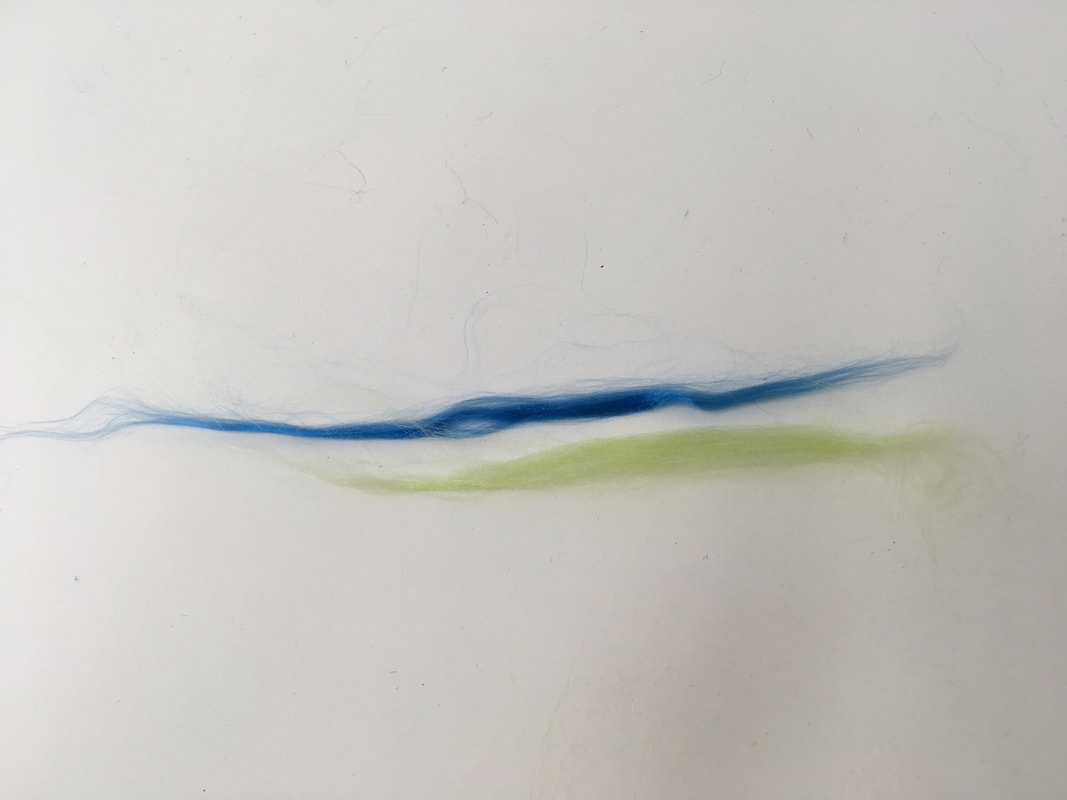

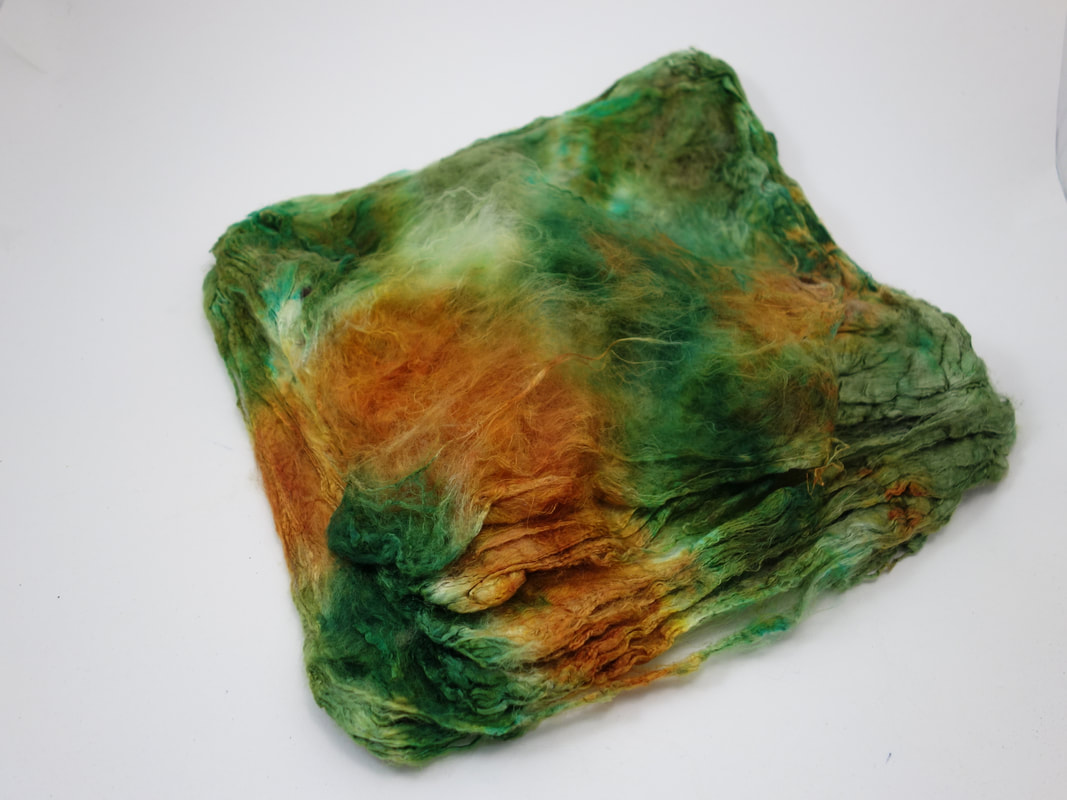

All of this is why I rarely dye to a recipe, particularly for complicated colourways. Our water supply can be incredibly variable. During the dry weather is was noticeably more acidic, and had more mineral content as the water was running through the soil more slowly. When we get a heavy spell of rain (like the 2 inches that have fallen over the weekend) the water becomes cloudy with mud. All these things change how the dyes behave, it's generally ok for very simple solid colours, but the ones that rely on complex colour interactions... just don't play ball when I dye them at different times of the year! I love silk. I love spinning it, love dyeing it, and just think it's such a wonderful fibre. But it has it's own terminology, and that can get confusing, someone asked me about it via email recently, so I thought a summary on the blog might be helpful for other people. First things first, what is silk? I sell 2 kinds of silk, and they're the kind of silk you're most likely to encounter as a spinner. All silk comes from silk worms. We're all familiar with the idea that caterpillars build a cocoon in which to turn in to a butterfly or moth. A silk worm does this by spinning out a strand of silk, similar in the way a spider spins out a web. The best quality, shiniest silk comes from a reeled cocoon.  By Claude Valette - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14980967 This produces a single strand of continuous silk. In order for this process to occur the cocoon must be processed before the moth emerges. However, this isn't wasteful, for people who process the silk the pupae is a valuable source of protein Each stage of further processing then goes on to make use of each lesser grade of silk, usually depending on consistency of the fibre length, and fibre type. There's next to no waste, everything gets used, and as spinners we use nearly all of the different grades of silk, either as top, brick, noil, or laps. The key exception to this, and explains their comparatively high price is silk hankies. These are a whole cocoon stretched over a frame, so they can't be processed to remove as much value from the different grades. Tussah vs Mulberry There are many types of moth who produce silk during their pupal stage. The most common are Tussah and Mulberry. Which moth provides which kind starts to get complicated, but generally Mulberry Silk comes from the Bombyx types of moth. This is sometime why Mulberry silk is also called Bombyx silk. Tussah silk comes from other types of moth. However, the types we usually have available as spinners are all farmed. So what are the differences that matter to us as spinners? These are both silk top. Bottom fibre in green is tussah, top in blue is mulberry. Mulberry is shinier, and much more compact. The tussah feels slightly toothier, with a little bit more wave to the fibre. Mulberry also has a longer, more consistent staple length. They will both spin in a shiny silk yarn. But for maximum shine I tend to go for mulberry over tussah. For blending with wool tussah is generally a better option, as it matches most wool staple length better. If you're a beginner, it honestly doesn't matter which kind of silk you choose to spin. A good quality Mulberry is in some ways easier than Tussah as the staple length is more consistent. However, Tussah can be slightly grippier, and easier to keep control of. There's no one correct fibre to begin with, try both! The main thing is to keep your hands far enough apart. Remember the staple length, if you hands get too close together they will be pulling on the opposite ends of the same piece of fibre. Silk is incredibly strong, you will never draft silk with your hands too close together. Some people advocate spinning silk from the fold with a backwards point of twist draft, and using a high twist level. Personally I spin straight from the end, using a regular short forwards draw, with relatively low twist levels (less than I would use for wool in a yarn of the same thickness). I find that gives me a yarn with maximum shine, and that's what I want from my silk! So experiment, find the way that works for you. Put-Ups Unlike wool which usually only comes in 3 commercially processed forms (combed top, roving or batts), there are a huge variety of ways in which silk is processed. The most common form of commercially dyed silk is as tops. This is a thin strip with all the original fibres aligned in parallel. It will be one of the forms of silk that is processed first, and as a result contains high quality fibres, of even consistency and quality. Both fibres in the photos above are combed top. The form of silk that I dye most often are Silk Bricks. In essence these are a thicker piece of combed top. They are called a brick because they are bundled up in to a dense rectangular form. They're easy to dye because you can spread them out. Dyeing Mulberry Silk top with hand painting techniques is a little like wrestling eels. Other forms of silk you'll come across - Silk Laps These are the waste from the processing. When the silk cocoons are carded the long fibres pass through the machines, but the shorter, clumpier fibres are left behind. They build up on the drums of the carding machine, and are then cut off in enormous sheets of textured silk fibre. You can spin them by themselves, and get a shiny textured silk yarn, but where they excel is for adding texture to blends. They also work wonderfully on the surface of felt. -Silk Noil These are the bits and pieces that are leftover inside the cocoon. They're lumpy and bobbly and short. They're great for adding a tweed texture to blends. Silk Hankies These are a whole cocoon, stretched over a frame. They look like a square handkerchief, hence the name. They are also sometimes stretched in a cap shape, which do exactly the same thing. Because they contain a fibres that are so long they can be a real battle to spin. The best way I found to spin them was mounted on a distaff, and in the same way that you would spin linen. However, they are versatile... You can knit with unspun hankies Photos here, More details here. I love using them directly on the surface of a piece of felt, they form a thin spiders web over the top of the wool. Knitty Article with more details on drafting them out, and spinning with them here. They will give you a textured, uneven yarn. Do not try to spin these on a smooth, even thread! Another way to use the is to take a pair of scissors to them, cut them in to strips that match the staple length of you wool, and card them with other fibres. Grades? Silk comes in various grades, particularly mulberry silk. The grade refers to the quality, both in consistency of fibre length, and the amount of straight, non-waste fibres that are present. Silk top is usually A-Grade, it's such a narrow strip of fibre that you will spot any inconsistencies. Silk Brick comes in several grades. A, B1, B2 and C are the most common. As a spinner, do not bother with anything less than A grade. It's just an exercise in frustration. If you do have inconsistent fibre then spinning from the fold with a point of twist draft helps to keep the fibre under control. However, what's coming in to the UK at the moment is of nowhere near the quality that it used to be. I have bricks from 6 years ago, and compared to the Silk Bricks I can buy now they're in every way superior. There seems to be a tendency for far too much seracin to be left in the fibres. Seracin is the glue that the caterpillar uses to glue the fibres together. It has to be removed before processing by boiling and use of an alkali. If it's not properly removed the machinery tends to damage the silk, and you also struggle to dye the fibre as it acts as a resist to water. As a result I'm switching away from dyeing bricks and am moving towards dyeing silk top. This seems to be better processed and better quality. I'm having it specially made in a thicker put-up to make it easier to hand paint so I can get the same colour effects as you're used to seeing on my silk bricks. If you want to read more about silk, then the Wormspit website is filled with useful information, but is quite in depth.

http://www.wormspit.com/images/silkandsilkworms.pdf http://www.wormspit.com/peacesilk.htm |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

Hilltop CloudHilltop Cloud- Spin Different

Beautiful fibre you'll love to work with. Established 2011 VAT Reg- 209 4066 19 Dugoed Bach, Mallwyd, Machynlleth,

Powys, SY20 9HR |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed